An interview with the musician about his tribute to Maradona, neighborhood culture, and his upcoming album

By Susan Villa

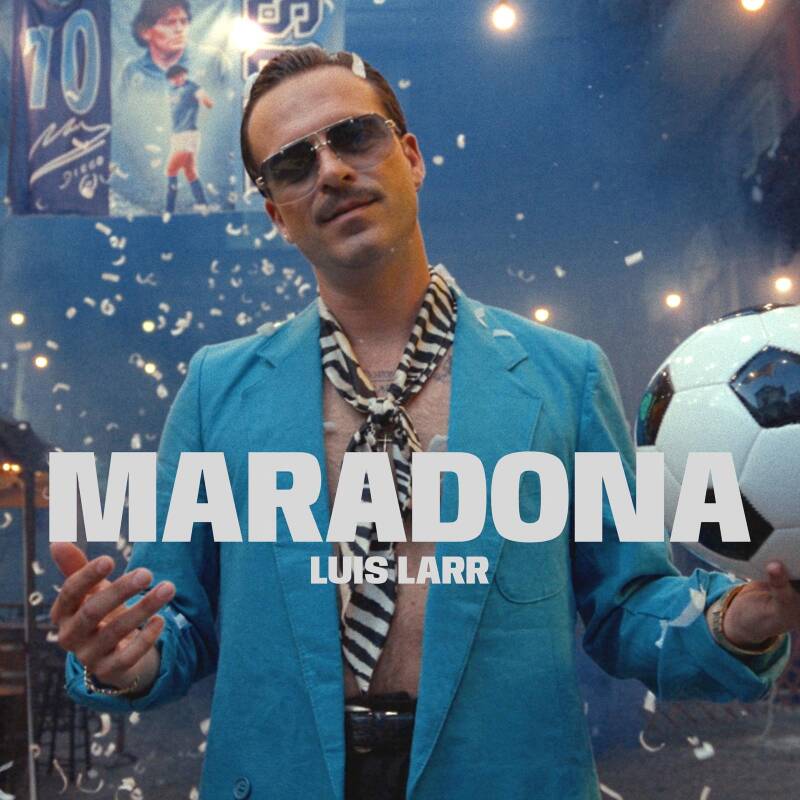

Luis Larr moves within a territory of his own, where music, image, and storytelling form a single language. A multidisciplinary artist and creator of worlds, his work draws from flamenco, Andalusian rumba, and Latin sounds to build a contemporary discourse that reclaims the street, elegance, and emotional truth. With Maradona as his calling card, Larr pays tribute to unrestrained passion, the popular myth, and a way of life that understands joy as an almost revolutionary act—always through a carefully crafted and deeply cinematic aesthetic.

In this interview, the musician reflects on the inspiration behind his new work, the symbolism of Naples as both a vital and creative setting, and the artistic evolution that culminates in his upcoming album, La clase no la da el dinero (Class Is Not Defined by Money). An honest dialogue about identity, roots, creative processes, and contemporary contradictions, in which Luis Larr champions authenticity over artifice and defends popular culture as a space of resistance, beauty, and rhythm.

1. “Maradona” blends Andalusian rumba, salsa, and a very marked gangster aesthetic. How did this track come about, and what did you want to express through this sonic fusion?

This track was born out of a somewhat obsessive period I had with Maradona—I watched documentaries, series… He was always a myth, a person who fascinated me. Maradona was always the South, excessive passion. He was a human being turned into a legend, ultimately overcome by passion. I identify with him in many ways.

I’m sure he would have loved it. I imagine Diego dancing to it and enjoying it at some party… I wanted to capture that party atmosphere—slightly gangster, but very fun. With good gangsters, haha… the bad ones don’t have the flair to have fun.

As for the fusion, I think southern Spain and the Caribbean have much more in common than we think. Among all the things that unite us, one of the most important is that warmth that brings us out onto the streets and makes us who we are. The joy of living can’t be bought. Happy, witty, forward-moving people who know how to figure things out. I believe that having street smarts doesn’t mean lacking class or good taste. I have a slogan that says, “What Latinos want to see and Spaniards want to dance.” I try to give each continent what it secretly admires about the other. Making it easier for Spaniards to dance with grounded beats and simple progressions, and creating Latin horn arrangements and breaks that invite movement. Speaking to each in their own language, so we can all enjoy ourselves together—because, once again, what unites us is far greater than what separates us.

With a street aesthetic, but with class—just as it should always be. Nowadays it seems you have to put on black teeth to “succeed.” Personally, I prefer those gentlemen from Buena Vista in light-colored suits, cigar in hand, shiny shoes. Or those flamencos in taverns, drinking wine in their suits and good shoes. A flamenco artist never wore bad shoes, haha.

2. The music video was shot in Naples, a city deeply linked to Diego Armando Maradona. What does this place symbolize for you, and what does it add visually and emotionally to the song?

The first time I went to Naples, I was blown away. I live in a movie all the time, haha—I’m always in cinema mode—and Naples is cinema: passion, chaos, color, the streets, the light, the people, il mare, il cielo blue. Maradona was crowned there. It couldn’t have been anywhere else. It was a dream, and it came true.

I imagined every scene in my head, and that’s exactly how it happened. Thanks to my people at Cuatro Amapolas—Ángel, Edu, Alex—, to Manu Suárez, the videographer, to Angie (my co-star), and to all the Neapolitans who made everything easier and more beautiful.

3. In your upcoming album, La clase no la da el dinero, there is a clear evolution toward a more urban and cinematic sound. Where are you creatively right now, and what sets this work apart from El último romántico?

The difference has been natural and progressive. In La clase no la da el dinero, musically speaking, the key difference has been Kasem Fahmi—a great producer and an even better person. We’ve gained impact, conceptual depth, and solidity, both in the musical discourse and in the visual one.

I wanted to be a bit more restrained and elegant, more cinematic. I wanted to let go of comedy a little—which is very hard for me, because I see comedy everywhere, haha—and use it in a more sarcastic way. Right now, I’m taking a pause. I more or less know what I want to do next, but… I need to stop and live a bit, haha.

4. You are a 360-degree artist: you compose, co-produce, and direct the visual concept of your projects. How important is it for you to control the entire creative process and build your own universe with each release?

It’s absolutely essential, because no one will care for your children the way you do. My creations are my girls, and that’s how I try to treat them. I would never let my beautiful girl go out badly dressed or neglected. Details matter—I try to conceptualize through symbols.

Also, simply because of budget constraints, I can’t always rely on a large team. Many times, creativity replaces budget. My “problem” is that when I’m in the studio or composing, I see the entire universe—I see scenes.

I say problem because creatively I never stop, and sometimes that is a problem. It frustrates me a lot not being able to bring everything in my head to life. I feel like I’m rotting creatively, and that’s a feeling I have to control and work on because it creates a lot of anxiety. If it were up to me, I would have already made two series, two films, and ten albums, haha… But little by little, I’m meeting the goals I’ve set for myself.

5. Your influences range from flamenco and Andalusian rock to Latin music and the Caribbean. How do these roots coexist in your music without losing authenticity?

Because purity can never be lost, and when you go back to the origin, you make fewer mistakes—or you’re more at peace with yourself.

When I feel lost, I try to return to my Seville or Cádiz, to sing rumba in bars to the rhythm of knuckles tapping on a solid wooden counter, with an ice-cold beer poured with flair, or to enjoy a good stew. To go to the beach, to the Caribbean, and spend time with the elders. Real people. Authentic people. There is more truth in a small market in those cities than in all of Madrid—with all my affection. Madrid is a wonderful city, beautifully diverse and with an incredible desire for fun, but it lacks truth. It’s a city where many people come to create a character and live a life that isn’t really theirs, and that worries me a lot. I don’t think it’s healthy to sell your true self for a Louis Vuitton bag and a couple of photocalls.

In big cities, the cracks in society are more visible. I feel the building is about to collapse; everything we’re creating is unsustainable. That’s why we have to return—with heart, eyes, and ears wide open—to real places. Truth is an act or a phrase spoken honestly and with rhythm (at the right moment).

6. Finally, what projects do you see on the horizon, and what can you tell us about the new chapter opened by La clase no la da el dinero?

I want to play, to work, to spread the message and the joy of the show everywhere—to lift hearts all over the world. That’s all I think about. Being joyful is a very serious responsibility.

Then God will say what I’m meant to do next.

Add comment

Comments