The Man

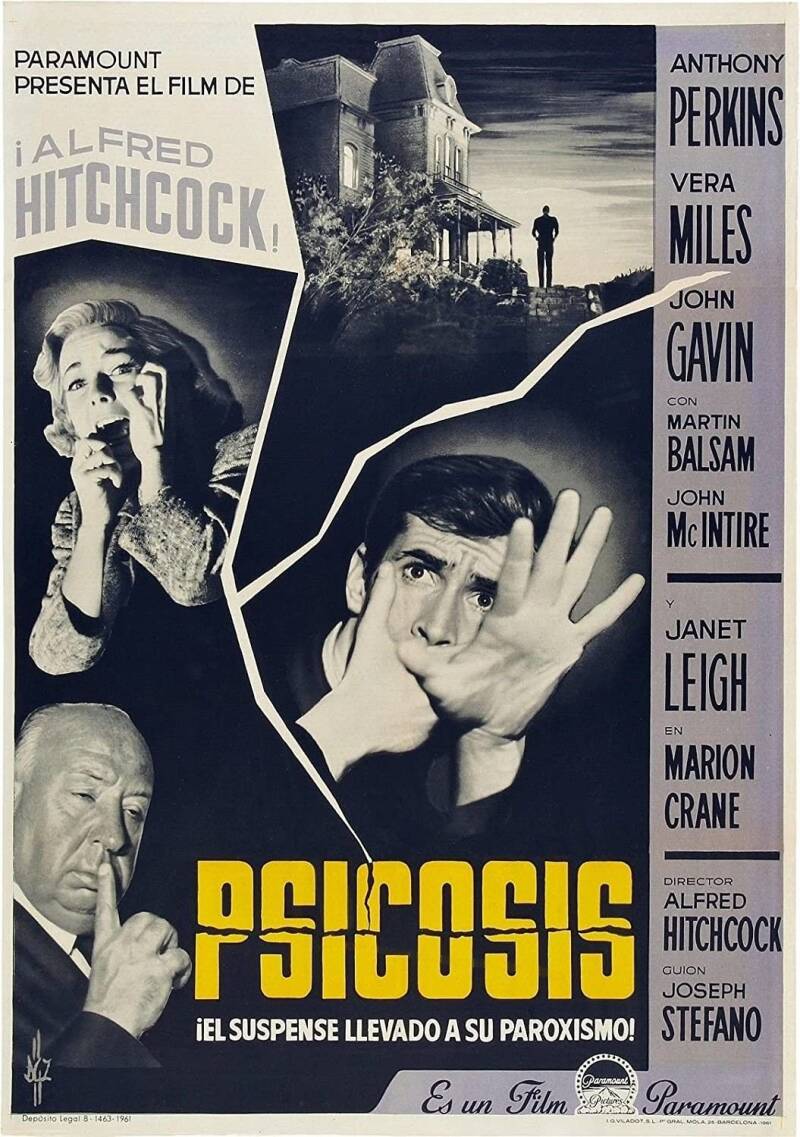

A mystery within another mystery, thus defined the author of Psycho, and his biographers have only been able to approach the epidermis of the person.

But the artist remains, with his work always renewed, with a handful of unforgettable images and characters… to what extent can we unveil a mystery that belongs only to Hitchcock? The 45th anniversary of his death is a good opportunity to remember one of the greatest artists of the 20th century.

Alfred Hitchcock was born on August 13, 1899, in Leytonstone, then a town near the foggy London of Sherlock Holmes, Jack the Ripper, and Scotland Yard, which today is a district of the East End of the British capital. His parents, William Hitchcock and Emma Jane Wehlan, owners of a grocery business, already had two children, William (1890) and Ellen Kathleen (1892).

From childhood, Catholic education shaped young Alfred’s personality. His first school was the Howrah Convent House. Two years later, another move took the family to Stepney. There the young boy enrolled in St. Ignatius College, founded by the Jesuits in 1894 and especially known for its discipline, rigor, and strict Catholic sense.

The school stay left a deep mark on Hitchcock. Education, the concepts of guilt and forgiveness, the sense of sin. Pure Catholic theology that the filmmaker would recreate in I Confess, The Wrong Man, Shadow of a Doubt, or Stage Fright.

Hitchcock had met Alma Reville, a girl his age, from Nottingham, petite and charming. Alma adored cinema and had worked at Film Company and the Famous Players company. On December 2, 1926, they married in a Catholic ceremony, settling on Cromwell Road in London.

In 1928, their daughter Patricia Alma was born; the family was a private refuge for the artist aside from his obsessions, creativity, and talent. Alma — the wife — and Patricia — the daughter who even acted in some films and plays — were vital reasons and anchors for Hitchcock to develop his career and conceive his masterpieces.

Hitchcock learned to make films during the silent film era, thus possessing the great secret that Truffaut spoke of. Like De Mille, Ford, Vidor, Henry King, Walsh, Leo McCarey, Chaplin, Fritz Lang, or Hawks, the author of Vertigo penetrated the mysteries of the wordless moving image, inventing the language with every film. A unique privilege of the pioneers of any art.

The Birth of an Artist

Blackmail (1930) was his first sound work (although it was made as a silent film with dialogue and sound effects added in a later edit). The story of a woman distressed by a crime committed in self-defense constitutes the first great display of the director’s talent.

Afterwards came his first triumphs: The Man Who Knew Too Much, The Lady Vanishes, The 39 Steps, or the redeemable Jamaica Inn, with an adorable and very young Maureen O’Hara and a brilliant Charles Laughton playing an evil judge who hides his vices and crimes behind the mask of his position.

Hitchcock sharpened an unparalleled technique, creating a particular universe full of personal touches: his brief and original cameos in films, portraits of women, the fragility of human relationships, fear and at the same time fascination with the unknown… But the British industry was too small for him; it was the time of the golden Hollywood.

Hitchcock arrived at the Mecca of Cinema and debuted with the great David O. Selznick, resulting in the unforgettable Rebecca (1940), Oscar for Best Picture and a beginning for history: “Last night I dreamed I went to Manderley again.”

Suspicion (1941) cleverly plays with the possibility that Cary Grant could be a murderer; it is the perverse ambiguity that also surrounds the masterful Shadow of a Doubt (1943) in which Teresa Wright discovers the monster hiding behind her adorable and charming uncle (Joseph Cotten).

Notorious (1946) depicted another morbid sensation: Cary Grant pushed his lover Ingrid Bergman to marry the suspect (Claude Rains) to fulfill the entrusted mission. And going to the very end of all purposes.

Spellbound, The Paradine Case, Lifeboat are new milestones, perhaps less perfect, but a playground for experiments (the dream sequences designed by Dalí, the action unfolding in a lifeboat) that refine the master’s hand. His style was already recognizable to any fan, but success, far from dulling his talent, pushed him to discover new fields.

The Creative Peak

Morality and murder run through the fascinating Rope (1949, with James Stewart). In I Confess Montgomery Clift plays a priest who must hide a criminal who confessed a murder in secrecy, and Strangers on a Train (a man proposes to another to exchange their murder plans so they cannot be discovered). Hitchcock had reached his creative summit.

The magic of a whole series of sensations with the camera, and especially on the faces and bodies of women, joins a prodigious sense of narrative, of suspense.

His gigantic popularity was greatly contributed to, starting in 1954, by the TV series Alfred Hitchcock Presents, in which the director acted as an original and often macabre and humorous host. He also personally directed some of the best episodes (Revenge, Bang! You’re Dead).

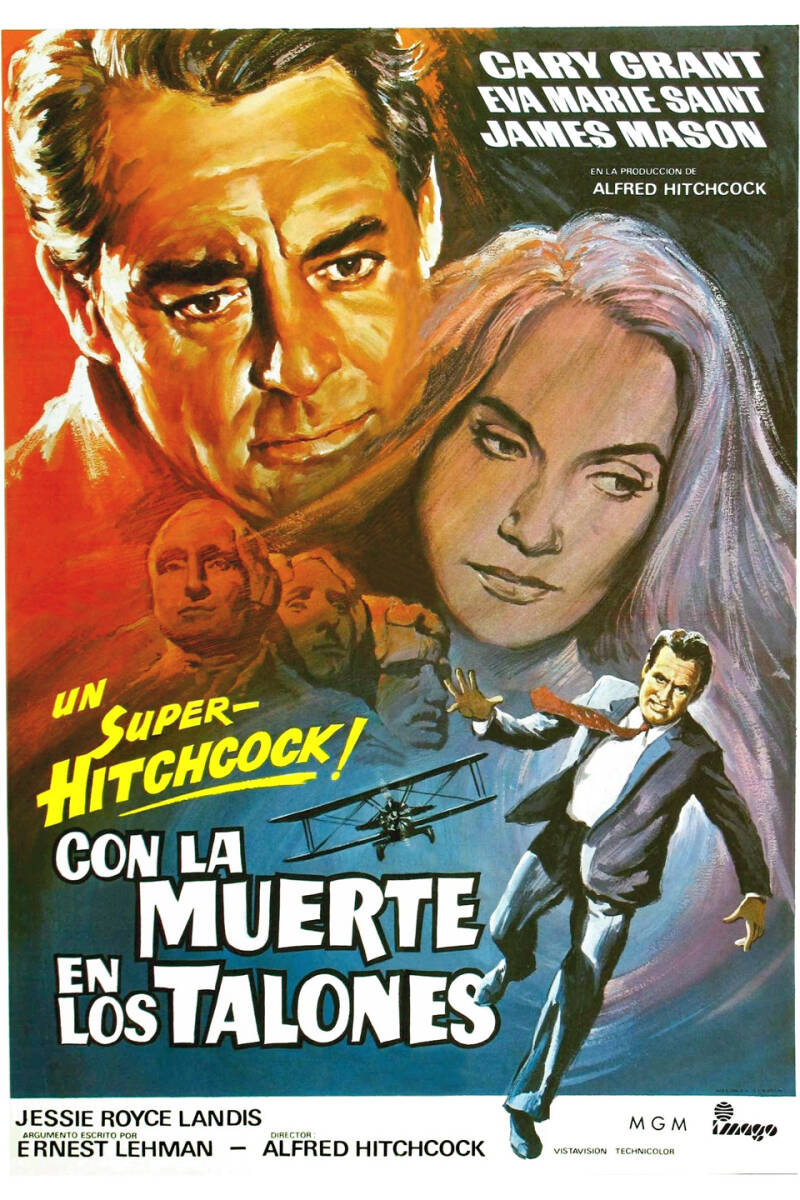

Masterpieces like The Wrong Man (Henry Fonda and Vera Miles in a true story, an innocent man confused with a dangerous criminal), divertissements like To Catch a Thief, with Cary Grant and Grace Kelly, and the extraordinary Rear Window (James Stewart and Grace Kelly in a reflection of the very passion of cinema: watching other people’s lives) lead to Vertigo (1958), with James Stewart and Kim Novak, one of the great artworks of the 20th century.

A portrait of necessary yet impossible love, a mirror of an obsession that causes the protagonist to abandon reality trying to make his dream come to tangible life, Vertigo is a captivating film, with an absolutely beautiful Kim Novak, capable of generating a thousand interpretations, of an unfathomable beauty that grows with every viewing.

North by Northwest (1959) with Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint represents the culmination of suspense cinema and Psycho (1960) opens the door to contemporary horror cinema. In the first, a brilliant puzzle full of unforgettable scenes is described. In Psycho, Hitchcock plays with the viewer’s identification with the protagonist (Janet Leigh) and after an anthology murder, he is able to change perspective and further increase the film’s interest. A true lesson in cinema.

The Woman

Hitchcock’s women compose a vital core of his work. If Alma Reville — on whom he had a strong sense of dependence — accompanied him all his life, Hitchcock sublimated in his best films a sensual vision of the woman he found attractive. Cold and seductive, blonde and distant but intensely carnal in dreamed moments.

Madeleine Carroll, Maureen O’Hara, Tallulah Bankhead, Laraine Day, Sylvia Sidney, Ingrid Bergman, Shirley MacLaine, Joan Fontaine, Teresa Wright, Jane Wyman, Janet Leigh, Marlene Dietrich, Alida Valli, Anne Baxter, Kim Novak, Vera Miles, Grace Kelly, Eva Marie Saint, Tippi Hedren, Julie Andrews, compose the mosaic of the feminine obsessions of an artist who knew how to make mystery his elegant trademark style. Among them stand out Ingrid Bergman (Spellbound and Notorious), Grace Kelly (Dial M for Murder, To Catch a Thief and Rear Window) and Kim Novak (Vertigo), joined by two director favorites, Vera Miles (The Wrong Man, Psycho, and for whom Vertigo was intended but pregnancy prevented her from starring) and Tippi Hedren (The Birds, Marnie), with whom he maintained a stormy and failed personal relationship.

Suspense and the Gaze

Suspense is the technical exercise that amazes in every film, the brilliant manipulation of time and space to maintain the viewer’s tension; women are the obsession, the imperishable female secret that Hitchcock vainly tries to possess and unveil. Death is the frequent destiny of this incapacity (Vertigo, Psycho, Topaz, Frenzy…).

Voyeurism is one of the most interesting themes since ultimately cinema is the power of the gaze over some glimpses of human life (in the brilliant expression of Julián Marías): Rear Window, that man stuck to a wheelchair by an accident (brilliant James Stewart) who watches from his apartment what happens in the building across, and of course Anthony Perkins — Psycho — when Norman Bates spies on Marion Crane as she goes to shower. Not forgetting Karl Malden watching Montgomery Clift in I Confess or Gregory Peck obsessed with the image of Alida Valli in The Paradine Case.

In Vertigo, James Stewart remains mesmerized by Kim Novak through the streets of San Francisco, the museums, the gardens, and his own universe between reality and fiction.

Following the success of Psycho, come The Birds and Marnie, two new masterpieces. After them, Hitchcock seems to restrain his inventiveness (despite the interesting Torn Curtain) as he becomes the target of attacks by some, especially after the splendid Topaz (1970), one of his most underrated works, a spy thriller that conceals a pessimistic view of life but also an effective anti-communism reflecting the cruelty and dehumanization of the Castro dictatorship in Cuba.

The finale

“Frenzy,” an explicit work about the violence of crime and the disturbances of the criminal, is the swan song of one of the great masters of cinema, although “Family Plot” (1975), curious and light, still followed, as well as the feverish work on his last project that he could not see realized: “The Short Night.”

On the morning of April 29, 1980, died the master and genius of horror, suspense, and mystery cinema, the man who created a style and a world of his own. Almost half a century later, his universe remains with all its appeal, even increased if anything, by the widespread decline of artistic talent in the Seventh Art.

His best works: Shadow of a Doubt, Rear Window, Vertigo, North by Northwest, Psycho... can be enjoyed both as first-rate cinematic exercises and as fascinating portraits of the human soul, its passions, its weaknesses, and its ambitions. Love and death in the foreground.

No one will ever—surely—unveil the artist’s mask, the veil of that mystery that captivates and attracts us. The secret of Alfred Hitchcock, on the level of the greatest filmmakers: John Ford, Cecil B. De Mille, King Vidor, Howard Hawks, or Fritz Lang.

Add comment

Comments